Oglethorpe and Religion in Georgia

Religion in the Georgia Charter

The original charter granted to the Georgia Trustees in 1732 contained only a few words about what religious practices would be allowed in the new colony.

And for the greater ease and encouragement of our loving subjects and such others as shall come to inhabit in our said colony, we do by these presents, for us, our heirs and successors, grant, establish and ordain, that forever hereafter, there shall be a liberty of conscience allowed in the worship of God, to all persons inhabiting, or which shall inhabit or be resident within our said provinces and that all such persons, except papists, shall have a free exercise of their religion, so they be contented with the quiet and peaceable enjoyment of the same, not giving offence or scandal to the government.

The Charter specifically denied Catholics the right to worship in the Georgia colony. Historically, the Spanish were Roman Catholic and Georgia’s founders feared that Catholic settlers might be sympathetic to the Spanish if conflict erupted between the two world powers. Prior to English settlement in Georgia, the Spanish operated multiple catholic missions on Georgia’s barrier islands and along the coast. Because of the ban, Catholicism did not take root in Georgia again until after the American Revolution. However, many other religious groups flourished in Georgia under Oglethorpe’s leadership.

First Jewish Settlers in Georgia

Although Catholicism was the only religion expressly forbidden in the charter, the Georgia Trustees also decided to forbid Judaism in the new colony, but the harsh realities of colonial life opened the doors for Judaism to enter Georgia.

The first summer the colonists lived in Savannah they suffered from the heat and illness that accompanied it. At one point, 60 colonists were dreadfully sick, and it was thought they wouldn’t be able to recover. There was no real doctor, except for Noble Jones who himself had taken ill. But fortunately a ship with Jewish passengers unexpectedly arrived, including a doctor, Samuel Nunez. Dr. Nunez went to work healing the sick, all of whom recovered, and the doctor refused payment for his services. Even though the Trustees expressly forbade Jewish people from settling in the new colony, Oglethorpe allowed the group to stay based on legal advice that the charter did allow religious freedom for all non-Catholics. Oglethorpe, in defiance of his fellow trustees, went further by allowing the Jewish immigrants to own land in the new colony. They founded the Temple Mickve Israel, the third-oldest Jewish congregation in America and the oldest in the South.

John and Charles Wesley

When Oglethorpe returned to Georgia from his first trip back to England he brought two young men with him to minister to the people of the new colony. John and Charles Wesley were brothers, and both were ordained ministers in the Church of England. John came to minister to the people of Savannah, and his brother Charles came to minister to the people of St. Simons Island, where Oglethorpe was planning another large community. These remarkable men were each destined for greatness. John Wesley would go on to found the Methodist Church, and his brother Charles would write more than 6,500 hymns.

Reverend George Whitefield

In 1738, Reverend George Whitefield arrived in Savannah and the plight of the orphans of the city came to his attention. He spent the next two years traveling around the colonies, raising money to open a home for Georgia’s orphans and by 1740 had a site and several buildings for the new orphanage. Many Georgians were critical of Whitefield’s method of raising children, claiming he was too harsh and wanted to convert the children to his brand of evangelical fanaticism, but he continued providing a home to children until his death in 1770.

When he died, he left the orphanage to the Countess of Huntington, a woman who had sponsored him while in England. The Countess continued the reverend’s work until her death in 1791, at which point the state of Georgia (because this was after the American Revolution) took over operations, and the school still provides a home and schooling for boys to this day.

Johann Martin Boltzius

Born in Forst, Germany, John Martin Boltzius is best known for strongly opposing slavery during the early years of the Georgia colony, and for serving as senior minister to the colony’s German-speaking Protestants called Salzburgers. The first group of Salzburgers sailed from England to Georgia in 1734, arriving in Charleston, South Carolina, on March 7, then proceeding to Savannah on March 12. Boltzius was met by General James Oglethorpe when the first group of Salzburgers arrived in Georgia from England in 1734. Oglethorpe assigned Boltzius and his group about twenty-five miles upriver in an area on Ebenezer Creek. Boltzius and the Salzburgers named their new settlement Ebenezer.

Boltzius and the Salzburgers also created the first Sunday school in Georgia in1734, followed by the first orphanage in 1737. The Salzburg community survived the American Revolution, Sherman’s occupation, and an 1886 earthquake. Boltzius’ Jerusalem Church houses the oldest Lutheran congregation America to conduct worship in its original building.

From the Source

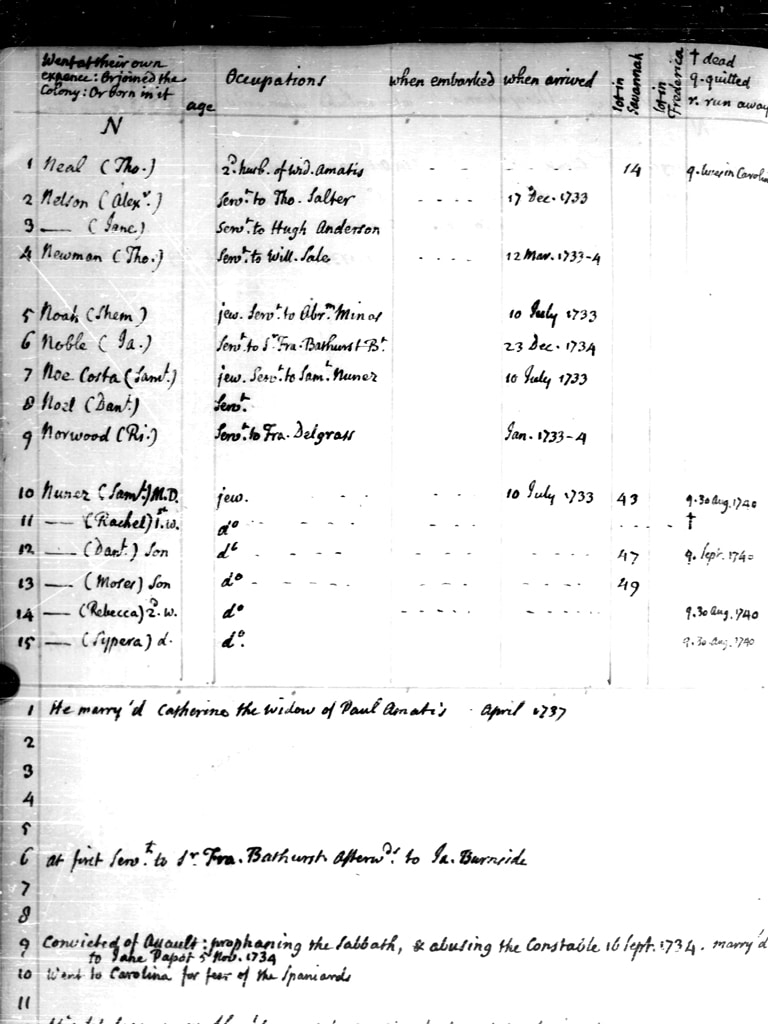

Earl of Egmont List of Early Settlers of Georgia, ca. 1743. Microfilm, MS 1395. This page from the Earl of Egmont’s list includes the entry for Dr. Samuel Nunez and several other early Jewish settlers.

Samuel Fayrweather Letter and Notes, MS 0249. Letter from Fayrweather, in Savannah, Georgia to Rev. Thomas Prince and Rev. Thomas Foxcroft, both of Boston, written May 25, 1748. Fayrweather provides a detailed account of the Bethesda Orphan Home founded by George Whitfield, including the positioning and architecture of the home, the surrounding grounds, and orchards, and the service, work, prayer, and education of the students.

The letter was transcribed and published in the Georgia Historical Quarterly.“A Description of Whitefield’s Bethesda: Samuel Faryweather to Thomas Prince and Thomas Foxcroft.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 45, no. 4 (1961): 363-66.