Collection Highlight

Richard Bowers Oliver Collection of Camp Wheeler Photographs

The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) recently purchased the Richard Bowers Oliver Collection of Camp Wheeler Photographs (GHS 2846) through the Lilla M. Hawes fund, established in 1978 by the GHS Board of Curators to honor Mrs. Hawes and her lifetime of dedication and contributions to Georgia history. Now processed, the collection of black and white photos provides rare glimpses into the everyday life of an American soldier at Camp Wheeler during World War II.

Camp Wheeler, named for Confederate Lt. Gen. and later United States Army Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, was constructed near Macon during World War I as a National Guard training camp for the 31st Infantry Division (N.G.), known as the “Dixie Division.” The division demobilized one month after the end of World War I, in December 1918, and Camp Wheeler was deactivated. The camp did not reactivate until 1940, shortly after World War II began.

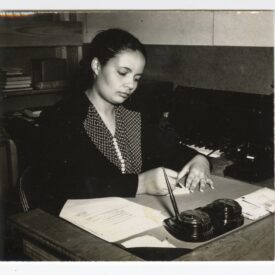

“The 900 plus images in the collection stand out for their portrayal of daily camp life in Georgia as infantry soldiers prepared for service in World War II,” said Nate Pedersen, GHS Manager of Archival and Reference Team. “Oliver was the camp photographer and did an excellent job of depicting the experience of camp life both for the soldiers who were training there and the civilians that worked at the camp.”

Camp Wheeler was used as an infantry replacement center between 1940 and 1945. New soldiers came there to undergo basic and advanced individual training. Once finished, they would replace combat casualties, dispersing to different units abroad. At the height of the training effort, the camp contained 17,000 trainees and 3,000 cadre personnel.

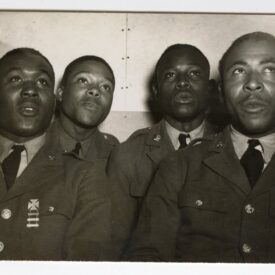

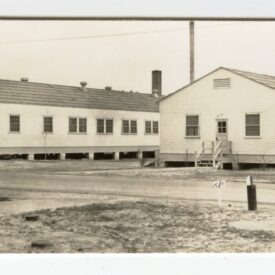

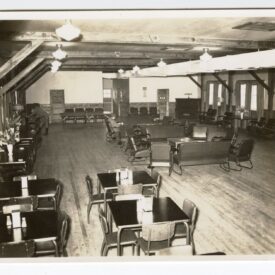

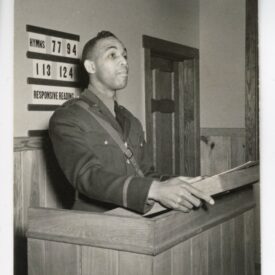

“Of particular note are the numerous photos of Black servicemen and Black civilian employees of the camp,” continued Pedersen. “For example, Oliver photographed the ‘Colored Service Club,’ which was a segregated social club for Black servicemen, highlighting the fact that Black people, who were willing to risk their lives for their country, were still not allowed to integrate socially with their White compatriots. We are glad that Oliver had the forethought to capture elements of Black camp life in his photographs, and we are happy to preserve these photographs here for future generations and make them accessible for research.”