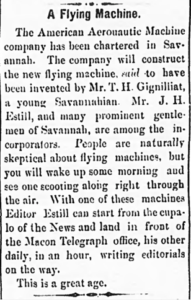

From the Daily Times-Enterprise, February 20, 1892

Nine years before Wilber and Orville made history at Kitty Hawk, flying machines were being developed at Georgia’s own American Aeronautic Machine Company. Chartered in 1892 for the commercial production and retail of airplanes, the company, the first of its kind, relied on the designs and research of T. H. Gignilliat.

“[…] Imagine on a cloudy or rainy day an aerial ship painted an almost invisible dull grey color floating up in the under side of the clouds till she sees that she is directly over some man-of-war or fortification. Imagine the aerial ship with the power of rising at will strait up miles high, of settling, of circling round and round or darting straight ahead at a rate of seventy five miles an hour. Suppose that she had on board five hundred or a thousand pounds of dynamite in one hundred pound packages. Don’t you think she could drop every package accurately and without being once visible to those below?” – T. H. Gignilliat, 1895

Thomas Heyward Gignilliat, a graduate of the United States Naval Academy, knew that flying machines were going to become the next revolutionary necessity of war. A brilliant mathematician, Gignilliat focused on developing a “heavier-than-air” craft that did not rely on balloons or gas. As a result, he had multiple patents for flying machines of various designs. His early designs focused on vertical lift, and many of his drawings feature the same elements found on helicopters today, such as main and tail rotors. Later, he developed bi-planes and tri-planes. Unfortunately, none of Gignilliat’s designs made it to sustained flight, and he was not able to complete his experiments. With no money for research, Gignilliat turned to the Venezuelan government, offering to produce for them a fleet of aircraft if they would fund his research. This plan never came to fruition, and Gignilliat never completed what he called his life’s work.

While others were simply trying to achieve flight, Gignilliat was looking beyond to military applications and how airplanes would become efficient, effective, and powerful tools of war. Dying in 1911, he did not get to see his predictions come true just a few short years later.

Visit the Georgia Historical Society to explore archival collection materials such as the Gignilliat Family Papers (MS2077), the Thomas Heyward Gignilliat and Thomas Heyward Gignilliat, Jr. Papers (MS 1124), A History of Savannah and South Georgia, and other items such as historical newspapers, journal articles, manuscripts, photographs, and more.