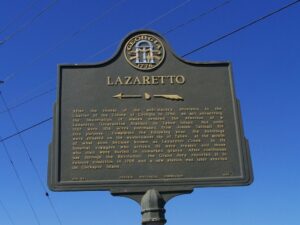

This week’s #MarkerMonday highlights the Lazaretto Marker on Tybee Island in Chatham County. In 1733 General James Oglethorpe, representing the Georgia Trustees, established the colony of Georgia. Located approximately eighteen miles away from the colonial capital Savannah, Tybee Island was fundamental to the development of the Georgia colony as it guarded the river used by ships as an entrance to Savannah. Following the repeal of the ban on African slavery in Georgia in 1749, Savannah became involved with the Atlantic slave trade. Because of Tybee’s proximity and importance to Savannah, the island played an imperative role in colonial slavery.

The term lazaretto, which is Italian in origin, is best defined as “pest” or “quarantine house.” The act of quarantining is traced to the late Middle Ages and the emergence of epidemic diseases, such as the bubonic plague. During the early years of quarantine, ships arriving from known areas of outbreaks were required to remain anchored off the coast of port cities for a certain period before passengers were allowed to disembark. Later, many American port cities established quarantine stations, or lazarettos, which housed people with possible diseases from the incoming ships until they no longer carried disease.

The first quarantine station in Savannah was established in the 1760s on the west end of Tybee Island, located by what is now known as Lazaretto Creek. Following the legalization of slavery in 1750 and the increased demand for enslaved labor on rice and sea island cotton plantations, Savannah’s merchants and planters directly imported slaves from West Africa on commercial vessels. Because of the extreme confinement and the lengthy voyage from West Africa to Savannah, the enslaved were subject to harsh conditions, often resulting in malnutrition and disease. In an effort to quarantine the enslaved who were at high-risk of spreading diseases, city officials built a quarantine facility, along with a keeper’s house, on Tybee Island in 1767. After physicians inspected the incoming ships for signs of diseases, the ill passengers, who were mostly enslaved, would be transferred to the Lazaretto and would remain quarantined there to allow the disease to pass. Those who did not survive were buried in unmarked graves near the Lazaretto on the west end of Tybee. Tybee Island’s Lazaretto was used until October 1785, when it was reported to be in ruinous conditions.

Explore the links below to learn more:

New Georgia Encyclopedia – Tybee Island

New Georgia Encyclopedia – Atlantic Slave Trade to Savannah

New Georgia Encyclopedia – Slavery in Colonial Georgia

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

Karen B. Bell. “RICE, RESISTANCE, AND FORCED TRANSATLANTIC COMMUNITIES: (RE)ENVISIONING THE AFRICAN DIASPORA IN LOW COUNTRY GEORGIA, 1750-1800.” The Journal of African American History 95, no. 2 (2010): 157–82. https://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.95.2.0157.

Sweet, Julie Anne. “TRUSTEES’ LETTER BOOK: 1745-1752.” In Colonial Records of the State of Georgia: Volume 31: Trustees Letter Book, 1745-1752, edited by KENNETH COLEMAN, 1–282. University of Georgia Press, 1986. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv21d62zd.6.

GHS houses several collections related to Lazaretto.

Julia Floyd Smith papers, 1957-1986.

Julia Floyd Smith and Strachan family papers, 1941-1993.

Slavery and rice culture in low country Georgia, 1750-1860 / Julia Floyd Smith.

Gender, race, and rank in a revolutionary age: the Georgia lowcountry, 1750-1820 / Betty Wood.

Erik Calonius research materials on the Wanderer (Schooner), 1830s-2008.

Plus many others.

The Georgia Historical Quarterly has published several article relating to the Lazaretto on Tybee Island, which can be accessed on JSTOR. If your library does not have access to JSTOR, you can go to www.jstor.org and create a free MyJSTOR Account.

Waring, Joseph I. “Colonial Medicine in Georgia and South Carolina.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 59 (1975): 141–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40580118.

Wax, Darold D. “‘New Negroes Are Always in Demand’: The Slave Trade in Eighteenth-Century Georgia.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 68, no. 2 (1984): 193–220. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40581222.

Krafka, Joseph. “MEDICINE IN COLONIAL GEORGIA.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 20, no. 4 (1936): 326–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40576461.