To further explore this year’s Georgia History Festival theme, “The United States Constitution: Ensuring Liberty and Justice for All,” January’s #MarkerMondays explore themes from Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, specifically how Georgians have regarded the Supremacy Clause and/or the Oath or Affirmation Clause.

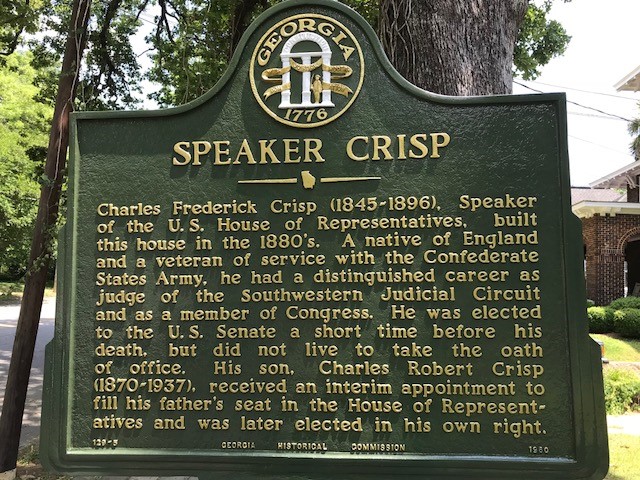

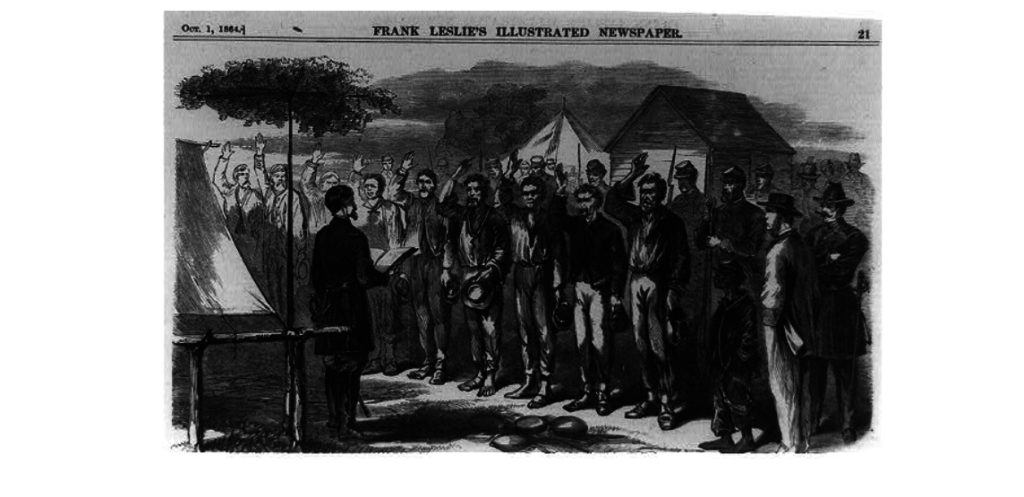

This week’s #MarkerMonday discusses Speaker Crisp, subject of a historical marker erected in Americus by the Georgia Historical Commission in 1960, and the modifications of the oath of office during and after the Civil War. At seventeen years of age, Charles F. Crisp volunteered for the Confederate Army in 1861. At the Battle of Spotsylvania in Virginia on May 12, 1864, U.S. troops captured Crisp and he remained a prisoner of war until after Lee’s surrender in April 1865. In exchange for release, Crisp and hundreds of others took an oath of allegiance to the U.S. Constitution and the United States.

Image credit: Library of Congress

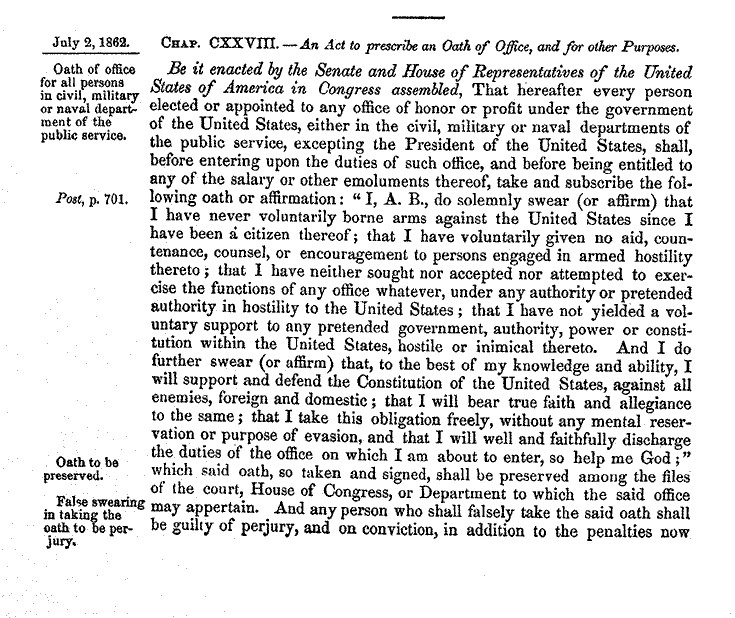

During this time, another oath, the oath of office for appointed and elected officials of the U.S. government, had undergone unprecedented changes. Before the Civil War, the oath of office had remained the same since the First Congress passed it as its first law in 1789: “I, A.B., do solemnly swear or affirm (as the case may be) that I will support the Constitution of the United States.” However, in 1862, Congress passed a law prescribing what became known as the Ironclad Test Oath, which began, “I, A.B., do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I have never voluntarily borne arms against the United States…” In 1864, the Senate made this oath mandatory for all Senators.

Following the Civil War, the return of representatives of former Confederate states to Congress required the oath to change again. While for a time members of Congress took different oaths depending on their activities during the war, in 1884, while Charles Crisp served in the U.S. House of Representatives, Congress established an oath of office absent of conditions related to prior actions, such as taking up arms against the United States. This oath is still in use today. This was emblematic of the period of sectional Reconciliation that followed the end of Reconstruction in 1877, when contentious racial issues became less important to white Americans than reunification.

Explore the links below to learn more about Charles F. Crisp and the oath of office.

New Georgia Encyclopedia “Charles Crisp (1845-1896)”

Library of Congress “Oath of Office”

Constitution Center: Article VI “Debts, Supremacy, Oaths, Religious Tests”

East Carolina University “Oath of allegiance to the Union”

GHS houses several collections related Charles F. Crisp.

Memorial addresses on the life and character of Charles Frederick Crisp : late a Representative from Georgia, delivered in the House of Representatives and Senate, Fifty-fourth Congress, second session.

JSTOR features articles on Charles F. Crisp and the oath of office. If your library does not have access to JSTOR, you can go to www.jstor.org and create a free MyJSTOR Account.