To further explore this year’s Georgia History Festival theme, “The United States Constitution: Ensuring Liberty and Justice for All,” and in recognition of Black History Month, February’s #MarkerMondays discuss amendments and laws within the context of the struggle for human and civil rights in Georgia.

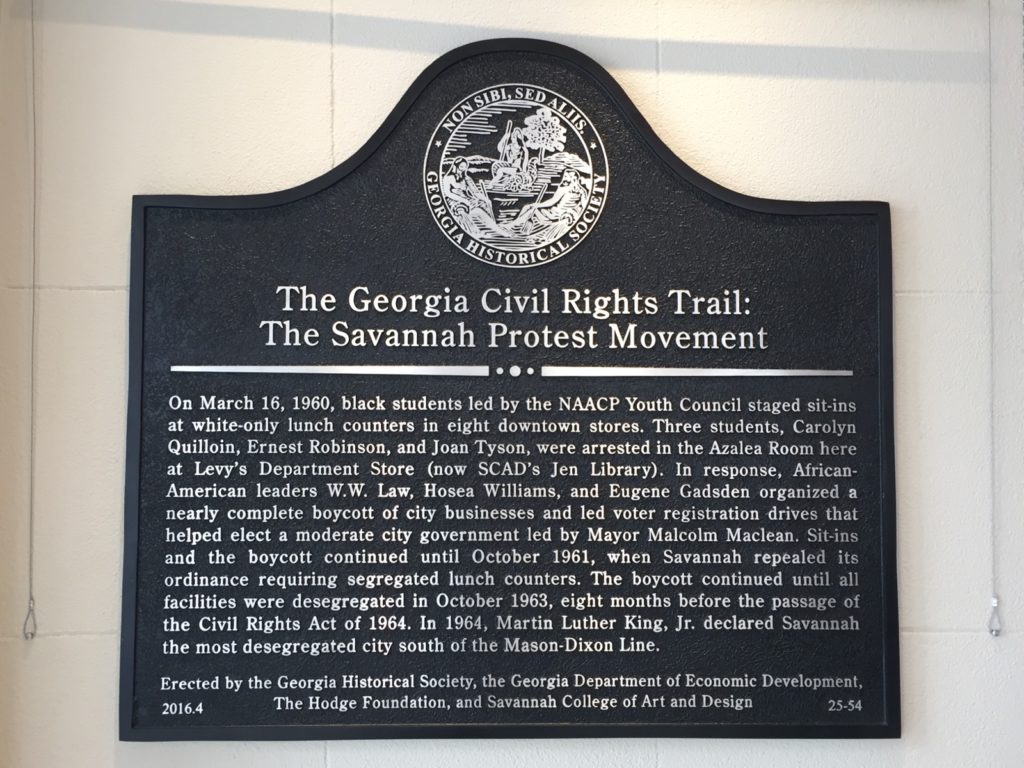

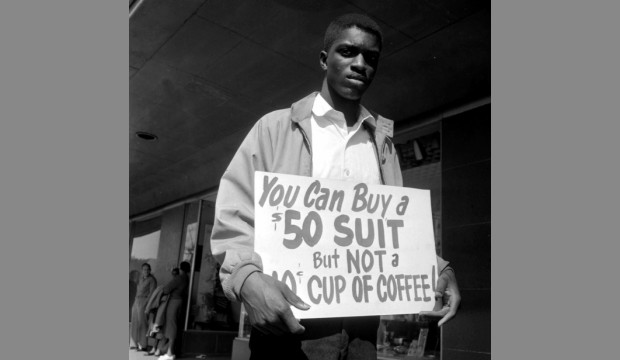

This week’s #MarkerMonday explores the Savannah Protest Movement and its participants’ ability to desegregate Savannah by 1963, eight months before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Inspired by the “Greensboro Four” who began successful sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, black students led by the NAACP Youth Council staged sit-ins in Savannah on March 16, 1960. The consequential arrest of three students at Levy’s Department store sparked an enduring movement.

Although a part of the larger Civil Rights Movement, the Savannah Protest Movement was uncommon, especially in its ability to exert continuous pressure on white power structures over an extended period. This success was largely due to the African-American leadership’s ability to mobilize a network of community resources at the local level. Organized by the NAACP, the Chatham County Crusade for Voters (CCCV) had established an African-American voting bloc that by 1962 included 57 percent of eligible black voters in Savannah, who were invested in racial equality. Protest leaders also organized citizenship schools focused on adult literacy programs, so that African Americans could pass a literacy test meant to deny voter registration, but which also served as a resource for recruiting people who filled both active and supportive roles in the ongoing movement. The students, who were often between the ages of 30-50, supported their younger teachers’ protests by preparing meals, housing out-of-town protesters, and contributing financially.

Courtesy of Savannah Morning News

Local high school and college students also provided large numbers of active protesters, and organizers recruited working class and unemployed African-American men on street corners, in pool halls, and at bars. Meanwhile, local churches served as safe places where activists could conduct public meetings and coordinate efforts.

With a continuous resupply of committed active protesters and a supportive network, the Savannah Protest Movement leadership and activists succeeded in waging a long, persistent campaign that ended segregation across Savannah on October 1, 1963.

Explore the links below to learn more about the Savannah Protest Movement and the struggle for human and civil rights.

Today in Georgia History “Civil Rights Act of 1964”

New Georgia Encyclopedia “Civil Rights Movement”

GHS houses several collections related to the Savannah Protest Movement and the struggle for human and civil rights in Georgia.

W.W. (Westley Wallace) Law speech on audiocassette and transcriptions, 1984.

W. W. (Westley Wallace) Law letter, 2001.

Ethel Hyer family papers, 1924-1980.

Brooks Creedy collection on Grace T. Hamilton, 1965-1984.

The Georgia Historical Quarterly published an article related to the Savannah Protest Movement which can be accessed on JSTOR. If your library does not have access to JSTOR, you can go to www.jstor.org and create a free MyJSTOR Account.

A City Too Dignified to Hate: Civic Pride, Civil Rights, and Savannah in Comparative Perspective

Further JSTOR reading.

Upheaval in Savannah: The Protest Cycle of a 'Short' Civil Rights Movement