This week’s #MarkerMonday discusses world-famous sculptor Gutzon Borglum and the ways in which his art reflects early 20th-century American values. In the early 1900s, Borglum focused on developing a uniquely American style of art steeped in American values and achievements. One of those achievements was the emergence of the United States as a budding power on the world stage after the Civil War. Borglum began exploring what he called “the emotional impact of volume,” and in 1908 carved a 40-inch marble bust of Abraham Lincoln that is displayed in the rotunda of the United States Capital Building. Interestingly, it was the Lincoln sculpture that gained Borglum the notoriety which inspired Helen Plane of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to contact him about sculpting General Robert E. Lee’s head on Stone Mountain. Borglum surveyed the mountain in 1915 and instead proposed a precipitously larger sculpture of Confederate leaders trailed by an army.

Seemingly an odd juxtaposition of subjects, both works were similar in that the size and disposition would have the effect of portraying Lincoln and the Confederate leaders as larger-than-life Americans. Borglum was raised in the post-Reconstruction era, a period in which the U.S. was more concerned with regional reconciliation, American expansion, and national identity and power than securing the civil, political, and social rights of African Americans. Borglum himself was both a Republican who admired Lincoln and a Klansman. Furthermore, by the 1910s and 1920s, Southern proponents of Lost Cause mythology dominated historical and fictional interpretations of the Civil War and Reconstruction in the South and enjoyed large pockets of influence and support throughout the country. Borglum’s proposed immortalization of Confederate forces thus gained widespread support, and the subjects and scale became symbols of American nationalism and grandeur.

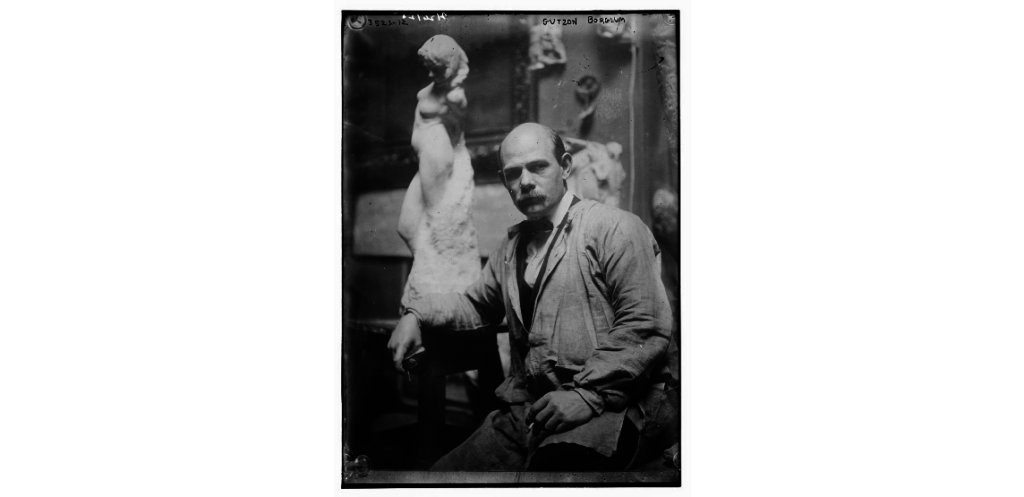

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/resource/ggbain.19378/

However, only the influence of Borglum’s vision remains. In 1925, the Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Association (SMCMA) fired Borglum over internal disagreements, and the Association subsequently blasted Borglum’s work off the mountain’s face. Borglum traveled to the Black Hills of South Dakota and began carving another emblematic—and ultimately controversial—monument to American culture: Mount Rushmore.

Explore the links below to learn more about Gutzon Borglum and Stone Mountain.

Today in Georgia History “Stone Mountain Carving”

National Park Service “Sculptor Gutzon Borglum”

New Georgia Encyclopedia “Stone Mountain”

GHS houses several collections related to Stone Mountain and the Ku Klux Klan.

Carswell family papers, 1861-1963.

Constitution and laws of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (incorporated)

Ku Klux Klan headgear and certificate, 1929.

The Georgia Historical Quarterly published an article about Gutzon Borglum and Stone Mountain which can be accessed on JSTOR. If your library does not have access to JSTOR, you can go to www.jstor.org and create a free MyJSTOR Account.

Granite Stopped Time: The Stone Mountain Memorial and the Representation of White Southern Identity