by W. Todd Groce, Ph.D.

There is a common misconception that historical organizations are a refuge for those disillusioned with the present, a bastion for old fogies who prefer looking backward rather than forward. Any organization whose mission is the study of history must be enamored with the past, right?

In fact, just the opposite is true. The study of history is not about celebrating the past. It’s about understanding the present. History explains how and why the world we live in today was created. Armed with that knowledge and insight, we can make well-informed decisions about the future. Knowing where we’ve been gives us a road map for going forward.

It takes success, courage, and a strong dose of confidence in the future to study history and confront the past in an open and honest way, warts and all. Conversely, defeat, fear, and a sense of decline usually prevent us from facing up to reality and lead us to construct a mythic past where the world was a better place (the post-Civil War myth of the Lost Cause comes to mind).

One need only look at the founding of the Georgia Historical Society for evidence of this connection between history (as opposed to myth) and faith in the future.

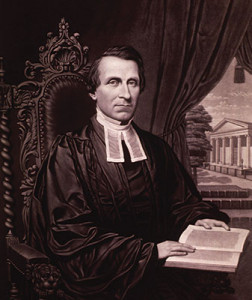

In the spring of 1839, three Savannahians—Episcopal divine William Bacon Stevens, renowned autograph collector Israel K. Tefft, and educator, scientist, and American Medical Association founder Dr. Richard D. Arnold—hatched the idea of an organization whose mission would be to “collect, preserve, and diffuse the history of the State of Georgia in particular, and of America generally.” In May of that year they held the first meeting of what was christened the “Georgia Historical Society,” the tenth state society founded in America (Massachusetts was first) and today the oldest continuously operated historical institution in the South.

Within a few months, membership had spread down the coast and as far west and north as Macon. The eighty-five charter members, who in December 1839 petitioned the Georgia General Assembly for articles of incorporation, read like a “who’s who” of Georgia society and included some of the most distinguished and progressive (for that time) leaders in the state. In addition to the original triumvirate of Stevens, Tefft, and Arnold, there were politicians like Congressman Eugene A. Nesbit and future U. S. Supreme Court Justice James Moore Wayne; Sea Island planters Thomas Butler King and James Hamilton Couper; and intellectuals like Augustus A. Smets, George White, and William A. Caruthers. The first president was John Macpherson Berrien, U.S. Senator and Attorney General of the United States under President Andrew Jackson.

In addition to their love of history, the one characteristic these men shared was that they had benefited from the explosive economic growth of the past few decades. Like today, Georgia in the 1830s was among the country’s fastest growing states. In the half century since it joined the Union in 1788, Georgia’s economy had expanded from one of the weakest to one of the strongest in the nation. The charter members of GHS were men of wealth and power who looked optimistically to the future. They and their state had reached a level of maturity and financial security that allowed them to turn their attention to more refined pursuits, to improving the world through education and research.

In Georgia the decade of the 1830s witnessed a technological, transportation, and economic revolution unrivaled until the second half of the 20th century. The spread of the cotton kingdom, the coming of the railroad, the birth of the modern two-party political system, and the discovery of gold in the northern part of the state and the consequent removal of the Cherokee Indians transformed Georgia into an economic powerhouse and fostered a sense of stability unknown since its founding.

As the state’s economy boomed, so too did its population. By the end of the decade Georgia was the ninth most populous state in the Union, as we are today. As thousands of white settlers and their slaves poured into the state and pushed the frontier (and Indians) westward, Georgia reached its modern boundaries, making it the second largest state in area east of the Mississippi River (today we are number one).

Clearly not everyone participated in or benefited from this prosperity. The invention of the cotton gin on a plantation outside Savannah forty years earlier only strengthened the institution of slavery and dimmed whatever slim hope there had been for its extinction and freedom for African Americans. The Cherokee suffered the same fate as the Creek before them, losing their land to the rapaciousness of a white society determined to exploit the state’s natural resources. Ironically the plight of Georgia’s African- and Native-Americans worsened as the prosperity of Georgia’s whites increased and contributed to the sense of optimism and stability shared by those who benefited from their oppression.

The rapid growth and accumulation of so much wealth earned Georgia a new nickname, first coined during this period: “The Empire State of the South.”

This decade of unprecedented expansion was capped by two events in 1839 that symbolized the state’s maturity and power: the building of a new governor’s mansion in Milledgeville and the founding of a state historical society in Savannah.

Why Savannah and not Milledgeville or Atlanta? Although the political capital of Georgia during the 1830s was in Milledgeville, the economic, social, and cultural capital was Savannah, the oldest and by far the largest city in the state—in fact, by modern standards it was the state’s only city. And it’s hard to believe, but in 1839 there was no Atlanta. Today, Georgia’s capital city is the center of power, money, and people, but 175 years ago that distinction belonged to Savannah. It was the only place that possessed the intellectual and financial foundation strong enough to sustain something as rarified as a historical society.

The 1830s share another similarity with the present. Just as we, today, are witnessing the passing of the World War II generation and are memorializing their accomplishments and sacrifice, our predecessors in the 1830s were watching the nation’s founding generation pass away. They, too, wanted to honor and preserve the record of those who participated in the most significant event (up to that time) in American history, prompting the founding of historical organizations across the country. It is no coincidence that the first artifact in the Georgia Historical Society’s collection, donated the year after its founding, was a drum carried during the Revolutionary War.

As they did 175 years ago, Georgians today feel a sense of confidence in the future. We are excited about our state’s prospects and our growing status as one of the wealthiest and most populous states in the Union. We still bear the scars of Jim Crow and struggle with its legacy; prosperity is still not shared by all. But we are moving on from the widespread poverty, demagoguery, institutionalized segregation, and racial strife that characterized so much of the 20th century.

Like our forbearers in 1839, it is our optimism, not our fears, that prompts us to turn to history—and to use its wisdom to tackle the problems of today and tomorrow. Economic and social progress is at last leading us to come to terms with our past and deconstruct the myths conjured by the post-Civil War generation. We no longer need to fashion a public memory that enables us to forget the uglier parts of the story. We have the self-confidence to take history in its totality, to look unblinkingly at those facets that make us uncomfortable. We strive to understand our failures as well as our successes in the hope that we can do better tomorrow. As it was once said, “how can the future be what it ought to be if we don’t tell the past like it really was?”

Over the last 175 years the fortune of the Georgia Historical Society has waxed and waned with the hopes and fears of the people it has served. Like the state we call home, the Georgia Historical Society of 2014 is stronger than ever. It has achieved a level of influence and affluence that its founders could only dream of. The ever expanding role GHS plays in pointing the way forward reflects the value Georgians place on their history—not as a nostalgic refuge from the modern world, but as a field of scholarly study and research that offers them context, perspective, wisdom, and hope to build a better future.

Georgia has changed deeply and radically since 1839. But the link between history and the future remains as strong today as it was 175 years ago.